[:en]

By: Prudence Jahja, S.H., LL.M. IP, and Andrew Diamond, J.D.

Commentary for The Jakarta Globe.

February 9, 2013 © The Jakarta Globe. All rights reserved.

Download a .pdf version of the article here.

Soon, a Singapore court will decide a lawsuit involving one of Indonesia’s most well known brands, with not only millions of dollars at stake but also ownership of the brand itself.

How Ku De Ta, the long-standing Bali beach club and an establishment known for its chic and laid-back demeanor, became embroiled in a hotly contentious, multiparty lawsuit 1,600 kilometers away from its sublime beachfront location in Seminyak is a story that every Indonesian brand owner should learn by heart.

It is a story that has important implications for doing business in this increasingly globalized world. And while this decision is eagerly anticipated by the parties and intellectual property lawyers who focus on trademarks and brand protection, for everyone else the decision itself does not matter, as the lessons to be learned from this case have been clear for quite some time, however the court rules.

It may be surprising to learn that there is no formal relationship between Ku De Ta in Bali and Ku De Ta at the Marina Bay Sands in Singapore – despite them both being high-end restaurant/lounge concepts with the same unusual name occupying prime real estate in their respective locations.

Indeed, the pivotal issue in the ongoing litigation is ownership over the Ku De Ta brand in Singapore. The question for the High Court of Singapore is: Who can legally register and own the Ku De Ta trademarks in Singapore? The answer is vital because, in determining ownership, the Court will decide who can exploit the brand for profit in Singapore, for example through lucrative licensing or franchise agreements.

While many contested facts remain to be resolved by the Court, a short summary of the dispute can be made. In 2000, a partnership group began operation of Ku De Ta in Bali, registering the “Ku De Ta” trademark for various goods and services in Indonesia, but not in Singapore. The restaurant and beach club soon became a highly popular destination, attracting foreign tourists and Indonesians alike. In 2004 and 2009, a now former member of the Bali partnership registered the Ku De Ta trademarks in Singapore separately from the partnership. Use of the Singapore Ku De Ta trademarks was ultimately licensed to the operators of Ku De Ta Singapore for the restaurant and club that now sits atop the Skypark at the Marina Bay Sands.

The Bali partnership is now seeking to cancel their former partner’s trademark registrations in Singapore, claiming that they are the legitimate owner of the Ku De Ta marks, whether in Indonesia or Singapore, despite their failure to register the marks in Singapore.

The former partner claims that through his company’s registrations in Singapore, he is the legitimate owner of the marks in Singapore and thus properly licensed them for use in Ku De Ta Singapore. The operators of Ku De Ta Singapore claim that they are just innocent third parties who unknowingly licensed the marks in good faith, a claim disputed by the Bali partnership.

If the Bali partnership’s claims are successful, the Singapore Court could cancel their former partner’s registrations; damages could be imposed; the Singapore club could be forced by the Court to change its name or, as requested by the Bali partnership, even to pay them a percentage of past profits. If, on the other hand, the Bali partnership’s claims are unsuccessful and dismissed by the Court, then they will have lost control of their brand in Singapore and the ability to profit from the use and reputation of the Ku De Ta name there.

There is no doubt that the stakes are high for the parties involved. But for the rest of us, the lessons are clear no matter who wins or loses. Above all else, the messy and costly litigation that has resulted from this dispute shows the absolute need for Indonesian businesses to be proactive in protecting their brands and products outside of the archipelago. Trademarks are territorial; that is, registering a trademark in Indonesia only provides protection in Indonesia.

Due to the increasing insignificance of national borders and surging international trade and travel, well-known local companies can be at risk of losing control of their brands overseas without a proactive protection strategy.

This is what happened to the Bali partnership, though with perhaps a little more intrigue than is usual. By not promptly registering its trademarks around the region after it began building its brand in 2000, the Bali partnership created the opportunity for another individual or company – rightly or wrongly – to register the Ku De Ta marks in Singapore.

Now, instead of spending perhaps less than $1,000 to register their marks in Singapore for 10 years of protection, the Bali partnership has had to spend tens of thousands of dollars, if not more, to litigate this issue in an attempt to “recapture” their marks, with no guarantee of success. This figure does not include the tremendous amount of time, energy and, no doubt, stress resulting from the dispute.

Indonesian companies should learn from this unfortunate situation and proactively protect their rights by registering their trademarks in countries where they do business or are likely to do business in the near future.

Almost all Asian countries operate according to a “first to file” system, which means that ownership of a trademark is given to the first person or entity to register that mark, not to whomever uses it first in the country. By proactively registering their company’s trademarks in relevant countries as soon as feasible, most likely after filing in Indonesia, Indonesians can protect their business’ reputation and profits.

As Indonesia’s economy continues to grow and homegrown businesses look outside the archipelago for future profits, responsible businessmen and women would do well to remember the lessons from the Ku De Ta case and not let control of their brand be overthrown by a coup d’état.

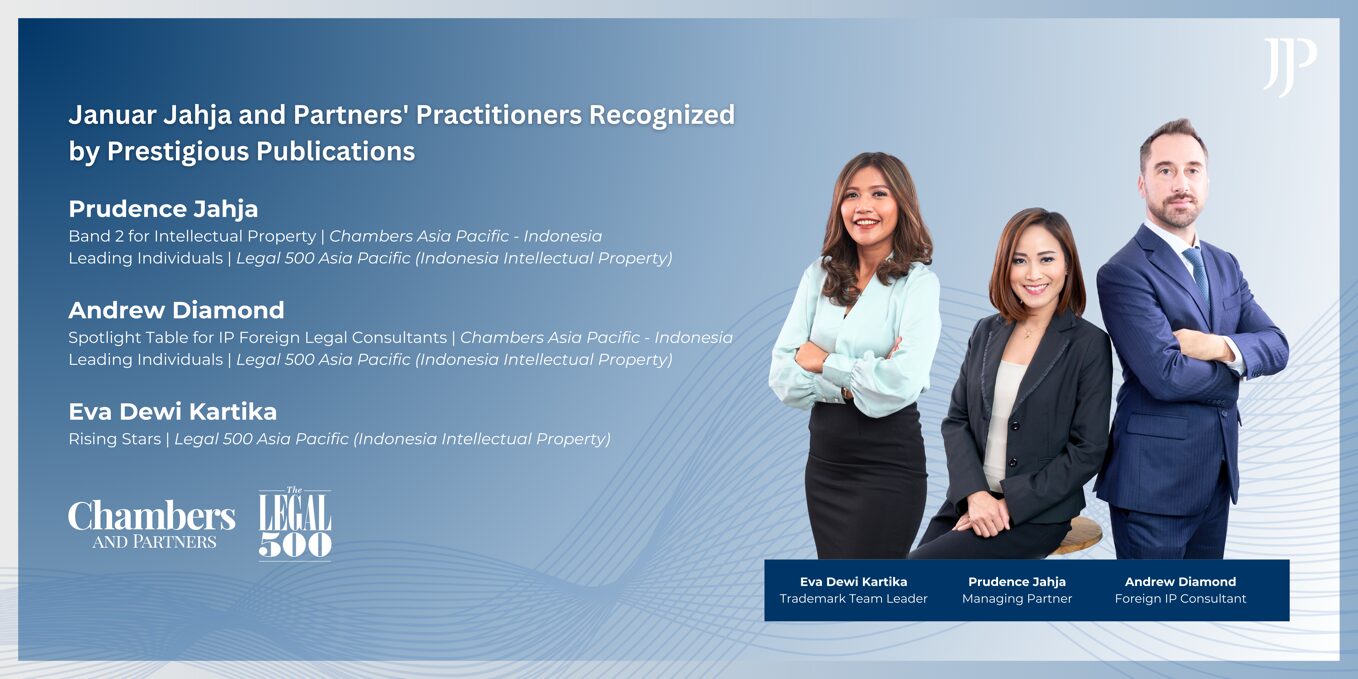

Prudence Jahja is an associate and Andrew Diamond is a foreign legal consultant at Januar Jahja & Partners, a Jakarta-based law firm specializing in intellectual property law. Januar Jahja & Partners is not involved with any group in the litigation of the Ku De Ta case.[:id]

By: Prudence Jahja, S.H., LL.M. IP, and Andrew Diamond, J.D.

Commentary for The Jakarta Globe.

February 9, 2013 © The Jakarta Globe. All rights reserved.

Download a .pdf version of the article here.

Soon, a Singapore court will decide a lawsuit involving one of Indonesia’s most well known brands, with not only millions of dollars at stake but also ownership of the brand itself.

How Ku De Ta, the long-standing Bali beach club and an establishment known for its chic and laid-back demeanor, became embroiled in a hotly contentious, multiparty lawsuit 1,600 kilometers away from its sublime beachfront location in Seminyak is a story that every Indonesian brand owner should learn by heart.

It is a story that has important implications for doing business in this increasingly globalized world. And while this decision is eagerly anticipated by the parties and intellectual property lawyers who focus on trademarks and brand protection, for everyone else the decision itself does not matter, as the lessons to be learned from this case have been clear for quite some time, however the court rules.

It may be surprising to learn that there is no formal relationship between Ku De Ta in Bali and Ku De Ta at the Marina Bay Sands in Singapore – despite them both being high-end restaurant/lounge concepts with the same unusual name occupying prime real estate in their respective locations.

Indeed, the pivotal issue in the ongoing litigation is ownership over the Ku De Ta brand in Singapore. The question for the High Court of Singapore is: Who can legally register and own the Ku De Ta trademarks in Singapore? The answer is vital because, in determining ownership, the Court will decide who can exploit the brand for profit in Singapore, for example through lucrative licensing or franchise agreements.

While many contested facts remain to be resolved by the Court, a short summary of the dispute can be made. In 2000, a partnership group began operation of Ku De Ta in Bali, registering the “Ku De Ta” trademark for various goods and services in Indonesia, but not in Singapore. The restaurant and beach club soon became a highly popular destination, attracting foreign tourists and Indonesians alike. In 2004 and 2009, a now former member of the Bali partnership registered the Ku De Ta trademarks in Singapore separately from the partnership. Use of the Singapore Ku De Ta trademarks was ultimately licensed to the operators of Ku De Ta Singapore for the restaurant and club that now sits atop the Skypark at the Marina Bay Sands.

The Bali partnership is now seeking to cancel their former partner’s trademark registrations in Singapore, claiming that they are the legitimate owner of the Ku De Ta marks, whether in Indonesia or Singapore, despite their failure to register the marks in Singapore.

The former partner claims that through his company’s registrations in Singapore, he is the legitimate owner of the marks in Singapore and thus properly licensed them for use in Ku De Ta Singapore. The operators of Ku De Ta Singapore claim that they are just innocent third parties who unknowingly licensed the marks in good faith, a claim disputed by the Bali partnership.

If the Bali partnership’s claims are successful, the Singapore Court could cancel their former partner’s registrations; damages could be imposed; the Singapore club could be forced by the Court to change its name or, as requested by the Bali partnership, even to pay them a percentage of past profits. If, on the other hand, the Bali partnership’s claims are unsuccessful and dismissed by the Court, then they will have lost control of their brand in Singapore and the ability to profit from the use and reputation of the Ku De Ta name there.

There is no doubt that the stakes are high for the parties involved. But for the rest of us, the lessons are clear no matter who wins or loses. Above all else, the messy and costly litigation that has resulted from this dispute shows the absolute need for Indonesian businesses to be proactive in protecting their brands and products outside of the archipelago. Trademarks are territorial; that is, registering a trademark in Indonesia only provides protection in Indonesia.

Due to the increasing insignificance of national borders and surging international trade and travel, well-known local companies can be at risk of losing control of their brands overseas without a proactive protection strategy.

This is what happened to the Bali partnership, though with perhaps a little more intrigue than is usual. By not promptly registering its trademarks around the region after it began building its brand in 2000, the Bali partnership created the opportunity for another individual or company – rightly or wrongly – to register the Ku De Ta marks in Singapore.

Now, instead of spending perhaps less than $1,000 to register their marks in Singapore for 10 years of protection, the Bali partnership has had to spend tens of thousands of dollars, if not more, to litigate this issue in an attempt to “recapture” their marks, with no guarantee of success. This figure does not include the tremendous amount of time, energy and, no doubt, stress resulting from the dispute.

Indonesian companies should learn from this unfortunate situation and proactively protect their rights by registering their trademarks in countries where they do business or are likely to do business in the near future.

Almost all Asian countries operate according to a “first to file” system, which means that ownership of a trademark is given to the first person or entity to register that mark, not to whomever uses it first in the country. By proactively registering their company’s trademarks in relevant countries as soon as feasible, most likely after filing in Indonesia, Indonesians can protect their business’ reputation and profits.

As Indonesia’s economy continues to grow and homegrown businesses look outside the archipelago for future profits, responsible businessmen and women would do well to remember the lessons from the Ku De Ta case and not let control of their brand be overthrown by a coup d’état.

Prudence Jahja is an associate and Andrew Diamond is a foreign legal consultant at Januar Jahja & Partners, a Jakarta-based law firm specializing in intellectual property law. Januar Jahja & Partners is not involved with any group in the litigation of the Ku De Ta case.[:]